by Melissa García Lamarca

This past 26-29 March Barcelona hosted the second international conference on economic degrowth for ecological sustainability and social equity, attracting hundreds of people from over 40 countries to learn about and collectively explore the subject. Faced with the multiple and complex challenges of climate change and social inequities (among others) due to Western consumption patterns, degrowth is about a voluntary reduction of the size of the economic system, proposing a framework for transformation to a lower and sustainable level and mode of production and consumption. Alongside this reduction of scale, degrowth is also about decolonising the imaginary, shifting values from ‘more is better’ towards qualitative relations and behaviour, as well as decommodifying and pushing back the market rationality that dominates most societies around the world.

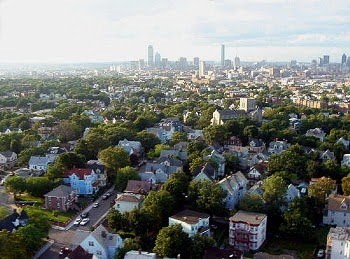

Credits: Photos by Melissa García Lamarca.

This past 26-29 March Barcelona hosted the second international conference on economic degrowth for ecological sustainability and social equity, attracting hundreds of people from over 40 countries to learn about and collectively explore the subject. Faced with the multiple and complex challenges of climate change and social inequities (among others) due to Western consumption patterns, degrowth is about a voluntary reduction of the size of the economic system, proposing a framework for transformation to a lower and sustainable level and mode of production and consumption. Alongside this reduction of scale, degrowth is also about decolonising the imaginary, shifting values from ‘more is better’ towards qualitative relations and behaviour, as well as decommodifying and pushing back the market rationality that dominates most societies around the world.

While the first international conference in Paris in April 2008 explored and proposed in essence this sort of a paradigm shift, largely through panel discussions and paper presentations, the heart of the Barcelona conference laid in 30 interactive working groups, each on an important topic related to economic degrowth for ecological justice and social sustainability. These working groups were tasked with collectively developing the important research and political proposals to move the degrowth agenda forward in various areas, from topics ranging from work-sharing, property rights and basic income/income ceilings to agro-ecology/food sovereignty, demography and cities.

With a diverse group of about 20 people from different backgrounds, countries and languages, the working group on Cities and Degrowth proved to be a challenging topic and conversation, starting from the basis of defining how a ‘degrowth’ city is different from an ecological or sustainable city. A wide range of issues were discussed, from infrastructure, city sprawl, resource production and consumption, urban agriculture and green spaces to having diversity while maintaining cultural identity, bottom up driven urban planning and if urban population limitation is compatible with the degrowth agenda – with concerns expressed over potential Malthusian interpretations of such issues. While there was general agreement on the need for example to roll back sprawl, remove automobile dependent development, create multifunctional spaces, generate energy locally and through small-scale sources, there was uncertainty on if degrowth equates to limits on urban densities or what to do about the control and power of developers. Were we talking about post-capitalist space? Or at least post-neoliberal spaces? Furthermore it was recognised that context is critical, as solutions for the ‘North’ are likely not the same as the ‘South’, and that scale, from town to megacity, must be taken into consideration.

The two political proposals, among over half a dozen, that emerged as priorities from the session included to 1) reshape and reform current cities instead of building (eco)cities and (eco)neighbourhoods from scratch and 2) to relocalise urban life with multifunctionality (i.e. public space as a commons) in mind. The two research proposals include the need to explore how the decentralisation of political power in the city relates to bottom-up processes and the degrowth agenda, addressing concerns around democracy and the concentration of power, and how Lefebvre’s right to the city – the right of all urban dwellers to take part in the production of the city, transforming social, political and economic relations in urban spaces – connects to degrowth.

So how do you think cities will look after degrowth? Can we plan for degrowth, and if so how (multifunctional urbanism, etc.)? The discussion continues, as most of us left with many more questions than answers.

Credits: Photos by Melissa García Lamarca.