by Ivan Valin

The reports from the International Climate Conference (4 Degrees & Beyond) being held in Oxford are, at least in the abstracts, ominous. It seems that while most governments have formally acknowledged the potential for a 2°C rise in global mean temperatures, some experts are beginning to think that this might be a tad conservative. This conference tries to open up the envelope to imagine the tipping points that could induce a 'runaway greenhouse effect'. A graphic from the keynote presentation shows that while this conference would be a yawner —

— it is probably still worth a few campfire stories of mass migration, ecosystem crush, drought and starvation. Horrors we've all been told of before, but this time the accompanying charts and graphs are uneasily plain (as opposed to sensational, Al Gore-on-a-cherry-picker stuff).

But I wanted to dwell on a comparatively insignificant story to come out of the conference, as reported by the Guardian yesterday. Tuvalu and the Maldives are doomed! Even in mildly higher seas, these and a few other island-states with no high ground will simply disappear. (Venice escapes this ending only with a massive public works project named "Moses") They will become 'ghost-states'. The victims of environmental disaster tend to migrate within the boundaries of their own state but this obviously isn't an option for island-folk. The small economies of these countries would obviously disappear, but would citizenship become virtual? Would island inhabitants form enclaves in landlocked countries not already overwhelmed by the reorganization of their own coastal populations?

Sea-level rise is a process, not an event, so the loss of entire countries could be orchestrated affairs. Certainly — and this is probably one of the points of the conference — with enough planning, economic and political structures can be put in place to minimize human suffering. And with human suffering out of the way, these states might even capitalize on the situation. Climate-change disaster tourism might spring up alongside today's scuba-diving outfits. With such a low gradient to the land, we could watch as each centimeter rise in the ocean floods entire districts. Ecotourists can marvel at rapidly transitioning ecologies. Will imaginative Tuvaluan city planners follow the tradition of Venetians and build a system of planks and stools to stay dry when the streets aren't or would colossal sand-bag levees eke out a few more years? Eventually, regional flights would have to bring in tourists on pontoon boats, of course, but it could be done to meet the demand of the new breed of urban snorkelers who will crawl through the city in flippers exploring exotic species of basement-coral.

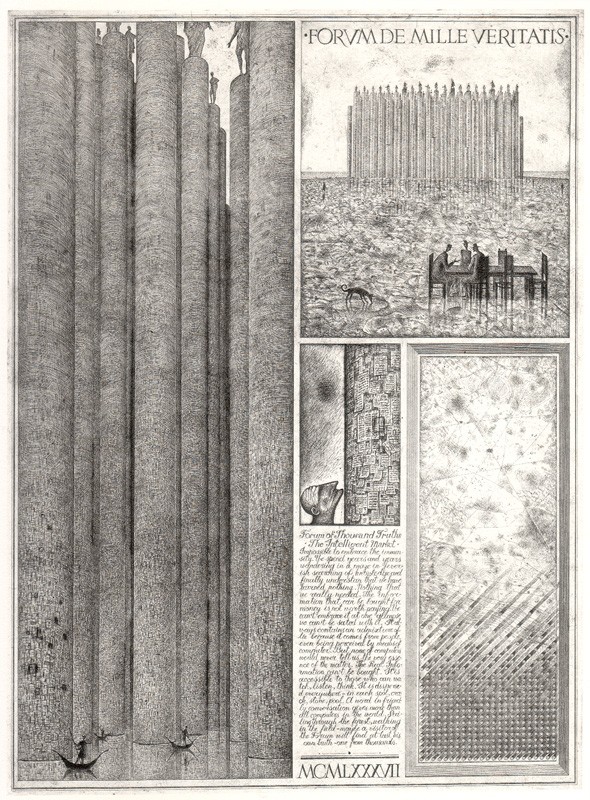

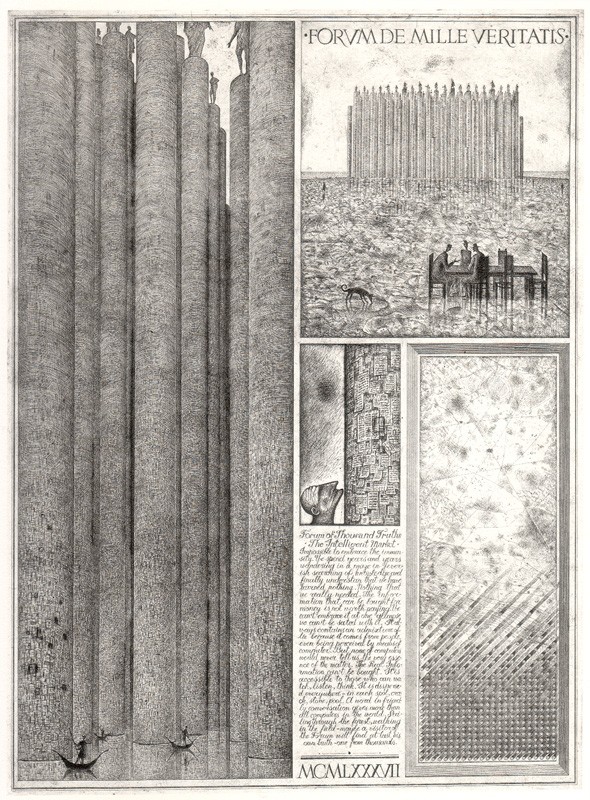

Perhaps this future is already told in one of the chapters of Calvino's Invisible Cities. Maybe it has already been planned and illustrated by the dark-architects Brodsky and Utkin.

Perhaps, after all, there is something graceful and sensual in the slow loss of a city to the sea. Atlantis redux.

The reports from the International Climate Conference (4 Degrees & Beyond) being held in Oxford are, at least in the abstracts, ominous. It seems that while most governments have formally acknowledged the potential for a 2°C rise in global mean temperatures, some experts are beginning to think that this might be a tad conservative. This conference tries to open up the envelope to imagine the tipping points that could induce a 'runaway greenhouse effect'. A graphic from the keynote presentation shows that while this conference would be a yawner —

— it is probably still worth a few campfire stories of mass migration, ecosystem crush, drought and starvation. Horrors we've all been told of before, but this time the accompanying charts and graphs are uneasily plain (as opposed to sensational, Al Gore-on-a-cherry-picker stuff).

But I wanted to dwell on a comparatively insignificant story to come out of the conference, as reported by the Guardian yesterday. Tuvalu and the Maldives are doomed! Even in mildly higher seas, these and a few other island-states with no high ground will simply disappear. (Venice escapes this ending only with a massive public works project named "Moses") They will become 'ghost-states'. The victims of environmental disaster tend to migrate within the boundaries of their own state but this obviously isn't an option for island-folk. The small economies of these countries would obviously disappear, but would citizenship become virtual? Would island inhabitants form enclaves in landlocked countries not already overwhelmed by the reorganization of their own coastal populations?

Sea-level rise is a process, not an event, so the loss of entire countries could be orchestrated affairs. Certainly — and this is probably one of the points of the conference — with enough planning, economic and political structures can be put in place to minimize human suffering. And with human suffering out of the way, these states might even capitalize on the situation. Climate-change disaster tourism might spring up alongside today's scuba-diving outfits. With such a low gradient to the land, we could watch as each centimeter rise in the ocean floods entire districts. Ecotourists can marvel at rapidly transitioning ecologies. Will imaginative Tuvaluan city planners follow the tradition of Venetians and build a system of planks and stools to stay dry when the streets aren't or would colossal sand-bag levees eke out a few more years? Eventually, regional flights would have to bring in tourists on pontoon boats, of course, but it could be done to meet the demand of the new breed of urban snorkelers who will crawl through the city in flippers exploring exotic species of basement-coral.

Perhaps this future is already told in one of the chapters of Calvino's Invisible Cities. Maybe it has already been planned and illustrated by the dark-architects Brodsky and Utkin.

Source: The Nonist

Perhaps, after all, there is something graceful and sensual in the slow loss of a city to the sea. Atlantis redux.