by Andrew Wade

As part of the Polis Three Questions series, we present an interview with Cassim Shepard, editor of Urban Omnibus, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Architecture at Columbia University and Poiesis Fellow at the Institute for Public Knowledge at New York University.

"Goregaon Railway Bridge," part three of Shepard's five-part series on street life in Mumbai.

Trained in filmmaking, urban geography and city planning, Shepard also produces non-fiction media about cities, buildings and places. He has exhibited his films at museums in Québec, Bologna, Milan, Portland and St. Louis, as well as at the 2006 Venice Architecture Biennale and the United Nations. His most recent video project, "Informal Urbanisms," chronicled life in six informal settlements around the world for the Cooper-Hewitt exhibition "Design with the Other 90%: CITIES."

Thank you for making time to answer our questions. Can you tell us about what you're particularly excited to be working on now, and what lies ahead for you?

For the past four years, I've been very fortunate to edit Urban Omnibus, The Architectural League of New York's online publication dedicated to defining and enriching the culture of citymaking. We present innovative projects in and perspectives on the built environment of New York City, essentially new or exemplary ways of interpreting or intervening in the urban landscape. So, what's particularly exciting for me is the opportunity to talk to creative thinkers in a wide range of disciplines — architects, urban planners, artists, community activists, city government officials, scholars, engaged citizens — and then to help connect the diverse ways people are acting locally to improve their city or neighborhood to a broader, international discourse of urbanism.

Aerial view of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, by Robert Clark. Source: Urban Omnibus

What does improving the experience of a waiting room in a central courthouse have to do with national shifts in the philosophy of the criminal justice system? What might the plans for a former shipbuilding facility on the Brooklyn waterfront teach us about how to encourage a sensible, 21st-century manufacturing policy for this country? How can the adventures of a thrill-seeking sewer diver inform our understanding of complex urban hydrological systems? I never get tired of thinking about those kinds of connections across different scales.

For me, this fits into a broader project that's motivated, in one way or another, every project I've been working on since I first started taking pictures in high school: trying to share my sense of awe at all the intentional choices that go into making human-made environments work, and trying to tease out how the accretion of those choices over time reflects particular cultural attitudes.

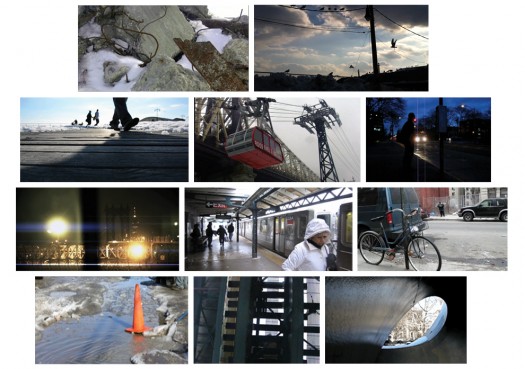

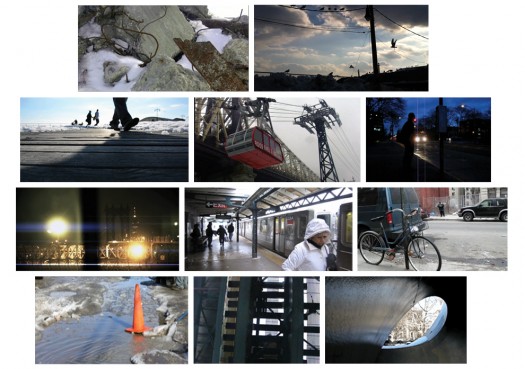

Video stills from Shepard's "Montage City" course at Columbia. Source: Urban Omnibus

After studying filmmaking in college, I spent several years making documentaries and video installations internationally with a couple pauses to study urban geography and urban planning. So after seven years living in many different places around the world and trying to tell many different kinds of stories audio-visually, I was very excited to take on something like Urban Omnibus that allowed me to explore one city, and its dense concentration of creative urbanists, in great depth.

"Shanghai" video montage by Shepard for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2006.

Now I think the time has come to continue and advance the work of connecting what's going on here in this city to what's happening elsewhere in the world. Discovering ways that cities — especially city governments, but also community-based organizations, consultancies, and non-profit organizations — can learn from each other's experiments and failures is a more complex challenge than it might seem. I'm interested in the role that sophisticated communication can play, whether it's high-quality journalism, visual art, online media, exchange programs for students as well as policymakers, or good old-fashioned storytelling.

What do you consider the most pressing issues we face as a society today, and how should we go about addressing them?

In a phrase: climate change. But naming that as an urgent challenge doesn't get us very far. Because it's not really one challenge, but a series of overlapping ones that include consumption habits, settlement patterns, energy production and distribution, infrastructure investment, manufacturing and supply chains — the list goes on.

Lower Manhattan on October 29, 2012, by Eric Chang. Source: Urban Omnibus

In the immediate aftermath of Superstorm Sandy last week, my colleague Varick Shute and I offered some thoughts to our readers that touched on the "new reality" of climate change in terms of infrastructure investment and scales of government. Climate change is so big and so planetary in scale that the role of the community is often obscured. We know what we're told as individuals about lightbulbs or gas mileage or plastic bags, and we know what we hope for from nation-states about carbon emissions standards or energy production. But the urban and community scales are a little harder to define in the climate-crisis conversation.

I'm especially interested in those infrastructural innovations that will bring greater flexibility and resilience to our urban environments and help to mitigate some of the effects of rising sea levels and stronger storms. As one example: retrofitting our impervious streetscape with permeable paving to absorb some of the stormwater flooding down our streets and off our rooftops, which overwhelms sewage systems. If federal governments aren't going to step up with coherent climate change policies, how can municipal governments leverage their unique assets — whether it's municipal infrastructure or an engaged citizenry — to make change?

"Archipelago," by Urban Omnibus, explores a day in the life of five New York neighborhoods.

What do you find inspiring?

Taking the subway from Brooklyn over the Manhattan Bridge every morning never ceases to amaze me. What I love most about living in a dense city like New York is the forced proximity to people unlike myself, with such different life experiences, cultures and perspectives. So I find the systems we've created for such a diverse group of people to share, to hold in common, pretty awe-inspiring for a number of reasons. And at the moment in my daily commute when the train comes out of the tunnel, somehow I always (no matter how late or preoccupied I might be) marvel simultaneously at the sociological story unfolding in my subway car, the infrastructural story of the subway system and the bridge, the natural story of the river and the shoreline, and the architectural story of Lower Manhattan's skyline. For me, thinking about how it got to be that way — and how it might work just a little bit better — really never gets old.

+ share

As part of the Polis Three Questions series, we present an interview with Cassim Shepard, editor of Urban Omnibus, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Architecture at Columbia University and Poiesis Fellow at the Institute for Public Knowledge at New York University.

"Goregaon Railway Bridge," part three of Shepard's five-part series on street life in Mumbai.

Trained in filmmaking, urban geography and city planning, Shepard also produces non-fiction media about cities, buildings and places. He has exhibited his films at museums in Québec, Bologna, Milan, Portland and St. Louis, as well as at the 2006 Venice Architecture Biennale and the United Nations. His most recent video project, "Informal Urbanisms," chronicled life in six informal settlements around the world for the Cooper-Hewitt exhibition "Design with the Other 90%: CITIES."

Thank you for making time to answer our questions. Can you tell us about what you're particularly excited to be working on now, and what lies ahead for you?

For the past four years, I've been very fortunate to edit Urban Omnibus, The Architectural League of New York's online publication dedicated to defining and enriching the culture of citymaking. We present innovative projects in and perspectives on the built environment of New York City, essentially new or exemplary ways of interpreting or intervening in the urban landscape. So, what's particularly exciting for me is the opportunity to talk to creative thinkers in a wide range of disciplines — architects, urban planners, artists, community activists, city government officials, scholars, engaged citizens — and then to help connect the diverse ways people are acting locally to improve their city or neighborhood to a broader, international discourse of urbanism.

Aerial view of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, by Robert Clark. Source: Urban Omnibus

What does improving the experience of a waiting room in a central courthouse have to do with national shifts in the philosophy of the criminal justice system? What might the plans for a former shipbuilding facility on the Brooklyn waterfront teach us about how to encourage a sensible, 21st-century manufacturing policy for this country? How can the adventures of a thrill-seeking sewer diver inform our understanding of complex urban hydrological systems? I never get tired of thinking about those kinds of connections across different scales.

For me, this fits into a broader project that's motivated, in one way or another, every project I've been working on since I first started taking pictures in high school: trying to share my sense of awe at all the intentional choices that go into making human-made environments work, and trying to tease out how the accretion of those choices over time reflects particular cultural attitudes.

Video stills from Shepard's "Montage City" course at Columbia. Source: Urban Omnibus

After studying filmmaking in college, I spent several years making documentaries and video installations internationally with a couple pauses to study urban geography and urban planning. So after seven years living in many different places around the world and trying to tell many different kinds of stories audio-visually, I was very excited to take on something like Urban Omnibus that allowed me to explore one city, and its dense concentration of creative urbanists, in great depth.

"Shanghai" video montage by Shepard for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2006.

Now I think the time has come to continue and advance the work of connecting what's going on here in this city to what's happening elsewhere in the world. Discovering ways that cities — especially city governments, but also community-based organizations, consultancies, and non-profit organizations — can learn from each other's experiments and failures is a more complex challenge than it might seem. I'm interested in the role that sophisticated communication can play, whether it's high-quality journalism, visual art, online media, exchange programs for students as well as policymakers, or good old-fashioned storytelling.

What do you consider the most pressing issues we face as a society today, and how should we go about addressing them?

In a phrase: climate change. But naming that as an urgent challenge doesn't get us very far. Because it's not really one challenge, but a series of overlapping ones that include consumption habits, settlement patterns, energy production and distribution, infrastructure investment, manufacturing and supply chains — the list goes on.

Lower Manhattan on October 29, 2012, by Eric Chang. Source: Urban Omnibus

In the immediate aftermath of Superstorm Sandy last week, my colleague Varick Shute and I offered some thoughts to our readers that touched on the "new reality" of climate change in terms of infrastructure investment and scales of government. Climate change is so big and so planetary in scale that the role of the community is often obscured. We know what we're told as individuals about lightbulbs or gas mileage or plastic bags, and we know what we hope for from nation-states about carbon emissions standards or energy production. But the urban and community scales are a little harder to define in the climate-crisis conversation.

I'm especially interested in those infrastructural innovations that will bring greater flexibility and resilience to our urban environments and help to mitigate some of the effects of rising sea levels and stronger storms. As one example: retrofitting our impervious streetscape with permeable paving to absorb some of the stormwater flooding down our streets and off our rooftops, which overwhelms sewage systems. If federal governments aren't going to step up with coherent climate change policies, how can municipal governments leverage their unique assets — whether it's municipal infrastructure or an engaged citizenry — to make change?

"Archipelago," by Urban Omnibus, explores a day in the life of five New York neighborhoods.

What do you find inspiring?

Taking the subway from Brooklyn over the Manhattan Bridge every morning never ceases to amaze me. What I love most about living in a dense city like New York is the forced proximity to people unlike myself, with such different life experiences, cultures and perspectives. So I find the systems we've created for such a diverse group of people to share, to hold in common, pretty awe-inspiring for a number of reasons. And at the moment in my daily commute when the train comes out of the tunnel, somehow I always (no matter how late or preoccupied I might be) marvel simultaneously at the sociological story unfolding in my subway car, the infrastructural story of the subway system and the bridge, the natural story of the river and the shoreline, and the architectural story of Lower Manhattan's skyline. For me, thinking about how it got to be that way — and how it might work just a little bit better — really never gets old.

+ share